Reversing an Oppo ozip encryption key from encrypted firmware

Reversing an Oppo ozip encryption key from encrypted firmware

A friendly and warm welcome to the start of my reversing blog in memory of Fravia’s ORC and requested by many real world people at the troopers conference.

In this lesson, we are choosing a rather easy target before we’re heading the more advanced targets such as Qualcomm Basebands. For today, we will concentrate on how to reverse engineer an aes encryption key for those nifty encrypted oppo firmware packages with “.ozip” extension.

We will use Ghidra for reversing, so if you haven’t installed it yet, take your time and grab your copy at https://ghidra-sre.org or for automated install on ubuntu/debian, use my installer over here.

As a start, in order to understand what we need, take a look at my repo implementing the ozip decrypter in python 3.x. Basically you can see that the encrypted ozip files always start with an header “OPPOENCRYPT!” at the first 12 bytes. The data to be decrypted starts at the offset 0x1050 and is usually encrypted using a simple aes 128 with mode ECB and a block size of 0x4000 bytes.

In order to test if our key is valid, we just take the first 16 bytes and try to decrypt it with our reversed 16 bytes key using the aes_dec function. If the key is the right one, we should see a regular zip header “PK…” or bytes “504B0304” in the hex editor after decryption.

So, in order to understand where those ozip files are decrypted, there are usually two types of suspects where we can search for. The first one, is the “/sbin/recovery” which will decrypt the firmware package in case of emergency under recovery mode. From within the running system, the “/vendor/lib64/libapplypatch_jni.so” handles firmware packages instead. The latter one should be easiest one to get as you probably won’t need root for it. So, enable the adb debugging on your target device, then run

~> adb pull /vendor/lib64/libapplypatch_jni.so

Having a look for the target device to be reversed “Realme U1 (RMX1831)”, there are some issues however. First one: I don’t own that device and I know nobody who does. Second one: All the device related stuff we find on the internet seems to be encrypted. So nothing to see here, huh?

As I tend to say RTFM or in this case: Never give up, never surrender. So I searched on the internet for a full firmware package. I found one with the filename “RMX1831_11_A.05_190118_6b900fa4.ofp” and opened it up in my lovely 010Editor (hexeditor). Entropy is our best friend and obviously we are lucky and only the first section seems to be encrypted. But the resembling structure is unknown and it doesn’t seem to fit the structures I am used to be.

So here we are, looking with our favorite hexeditor at that file, we finally see some sort of partition structure. The byte pattern “CAC30000” and “CAC10000” are normally used by android firmware for image reconstruction. Thus it allows us to search for a possible partition start and thus might help to find the vendor partition which we need. Over there I wrote a script for it (yeah bloody dirty hack, but who cares) :

ofp_extract.py (Outdated, see update below)

So we finally have our crafted vendor.bin and we are trying to mount it in linux. It simply doesn’t work. But you know, we’re not giving up, right ?

Ok, obviously I missed something, but the layout looks like ext4 but with pagesize of 4096 instead of 512, still kind of weird. Maybe another researcher has an idea and leaves a comment ? :D

Anyway, as we are real reversers, we know that the file we are interested into is an arm library and should start with an ELF header “.ELF”, has a size of approx 300-700K and it should contain the bytepattern “004C494243006C6962632E736F006C69626170706C79706174” (which is just the library export handler for libpatchapply_jni.so). We also assume the image was just build and never used in real life, so we can assume all data is in sequential order and not mixed up due to the way ext4 normally works with its nodes.

Using that belief, we first search for the bytepattern in our crafted vendor.bin using ofp_extract and yay, we got two hits at offsets 0x25B148EB and 0x28205157. I expected that, as we should have two libraries in the system, on for 32bit and one for 64bit. Now we are seeking for the beginning of the ELF, searching for “7F454C46” (“.ELF”) just above the offset 0x25B148EB, which results in a hit at offset 0x25B11000.

So we only need to find the end of the binary. Being aware of the ELF structure, we know that at offset 0x20 starting from the ELF header, there is the offset for the SECTION_HEADER_LENGTH, which should be at the end of the file (in our case, section header offset length is 0x06AFB4 in little-endian). And at offset 0x2E starting from the ELF structure we see the size of a section header is 0x28 bytes and at offset 0x30 we see there are 0x1B sections in total.

To conclude : 0x06AFB4 + (0x28*0x1B) = 0x6B3EC as file length based on the ELF header.

So we extract 0x6B3EC bytes starting from offset 0x25B11000 of our vendor.bin and store it as a file named “libapplypatch_jni.so”.

Update: Use this script to automatically extract either libapplypatch_jni.so or the recovery.cpio.gz which contains /sbin/recovery from any oppo ofp firmware file.

Once you got it, fire up ghidra. If you haven’t created a project, do it now. Then import “libapplypatch_jni.so” using File->Import File and double click on it. If being asked for analysing the file first, do so. Well done mate, it looks like a valid arm binary :)

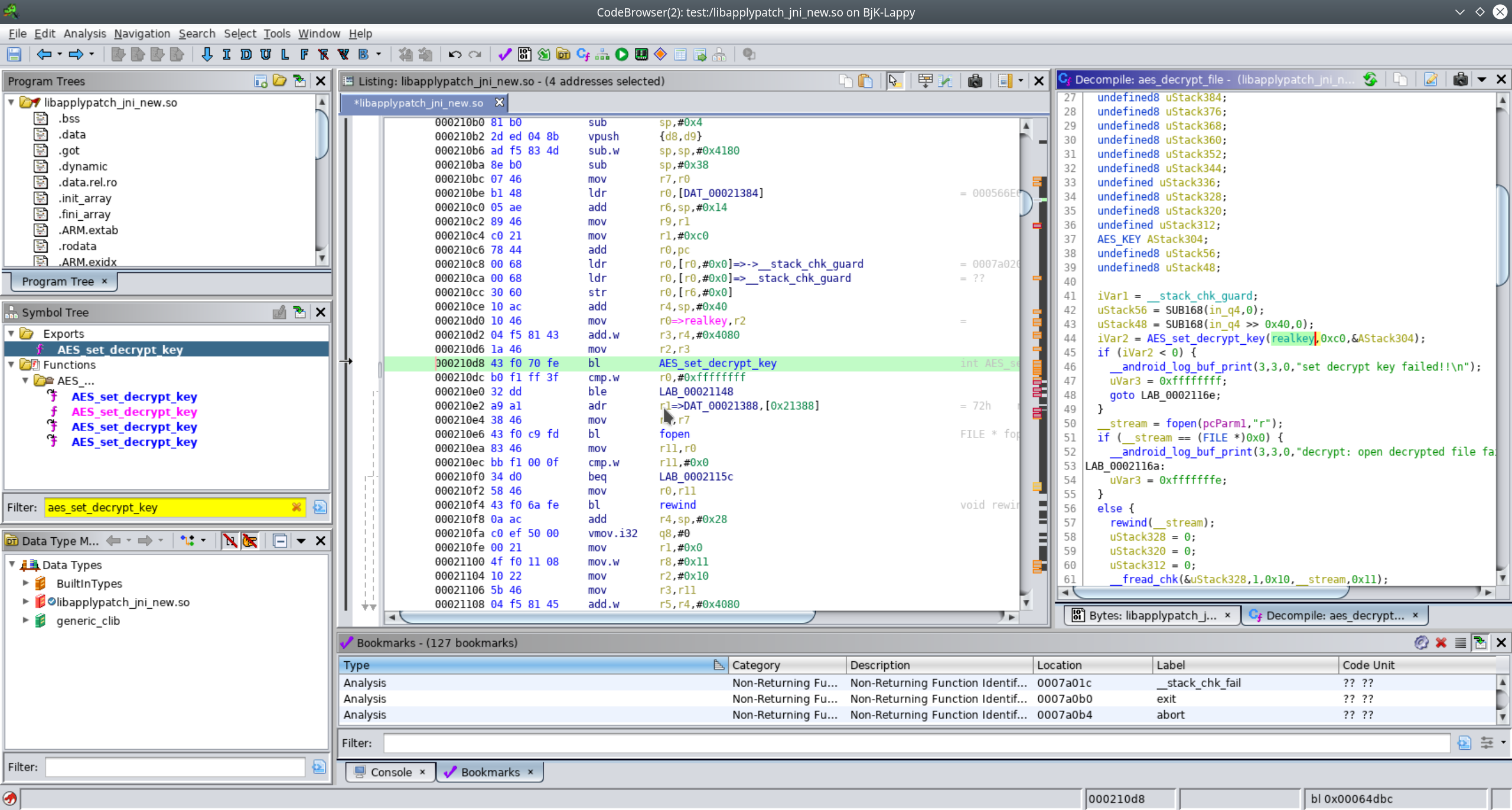

As we are searching for an aes key with 128bit (16 bytes), let’s have a look for the openssl standard implementation setting up an aes key for decryption, which is commonly used in native libraries : aes_set_decrypt_key. Enter “aes_set_decrypt_key” in the Filter option in the Symbol Tree in Ghidra. You will see that there is one hit in the Exports table. Doubleclick it so that it is shown in the Listing window. You can see by the looks at the registers, that the function has three parameters, which are “userKey”, “bits” and “key”. The latter is the key context, but as we are interested in finding the correct aes key, we choose the first parameter to be interesting.

Now we just need to trace back which function actually fills the first parameter of our beloved aes_set_decrypt_key function by having a look at the xrefs (just double click on them in the listing). Always stepping back in disassembly from one xref to another, we are hitting the code address 0x1c45c, then 0x64dc0, then 0x64dbc until we finally hit the code address 0x210d8 which has as an argument a pointer to an unsigned char array [16] called “realkey”.

Double clicking the realkey pointer, voilà, starting at 0x78034, we see an aes_key “d6cf….381e”. If you want to copy it, just enable the “Binary” view in Ghidra. After having a look at all the references to “aes_set_decrypt_key”, we find a total of six aes keys called “userkey”, “mnkey”, “mkey”, “testkey”, “realkey” and “utilkey”.

We ain’t got time to fully reverse the usage of each and every key, so we fit in the keys into the keys section of our python3 script decrypter, and try to decrypt an ozip file for this device.

bjk@Lappy:~/Projects/oppo_ozip_decrypt$ ./ozipdecrypt.py RMX1831EX_11_OTA_0070_all_UqwwgT6ye4J1.ozip

ozipdecrypt 0.3 (c) B.Kerler 2017-2019

Found correct AES key: acaa1e12a71431ce4a1b21bba1c1c6a2

Decrypting...

DONE!!

So it seems that the “userkey” is obviously the aes key needed to decrypt the oppo ozip files.

Mission accomplished :)

Stay tuned for following posts ….

Let me know what you think of this article on twitter @viperbjk or leave a comment below!